“Walking the plank” – was it historical reality or fictional myth?

The image of a pirate forcing a captive to “walk the plank” has become an enduring trope in popular culture. Depicted in numerous books and films, this gruesome practice is often associated with the ruthless and lawless world of pirates. However, it is crucial to distinguish between historical reality and fictional embellishments.

The golden age of piracy, which spanned roughly from the late 17th to the early 18th century, was a time of lawlessness and violence on the high seas. While pirates indeed employed various brutal methods to instill fear and maintain control, there is limited evidence to suggest that “walking the plank” was a widespread practice during this period.

Historical records indicate that pirates resorted to more efficient and expedient methods of disposing of their captives, such as marooning them on uninhabited islands or simply executing them on board. These methods allowed pirates to swiftly eliminate threats without the elaborate preparations associated with “walking the plank.” The absence of specific accounts mentioning this practice, despite ample documentation of pirate activities, suggests that it was not a commonly employed method of execution during the golden age of piracy.

Daniel Defoe first brought the practice into the public imagination in his 1724 book A General History of the Pyrates, where Defoe described ancient swashbucklers in the Mediterranean telling their Roman captives they were free to go if they followed the ship’s ladder into the waves to fend for themselves.

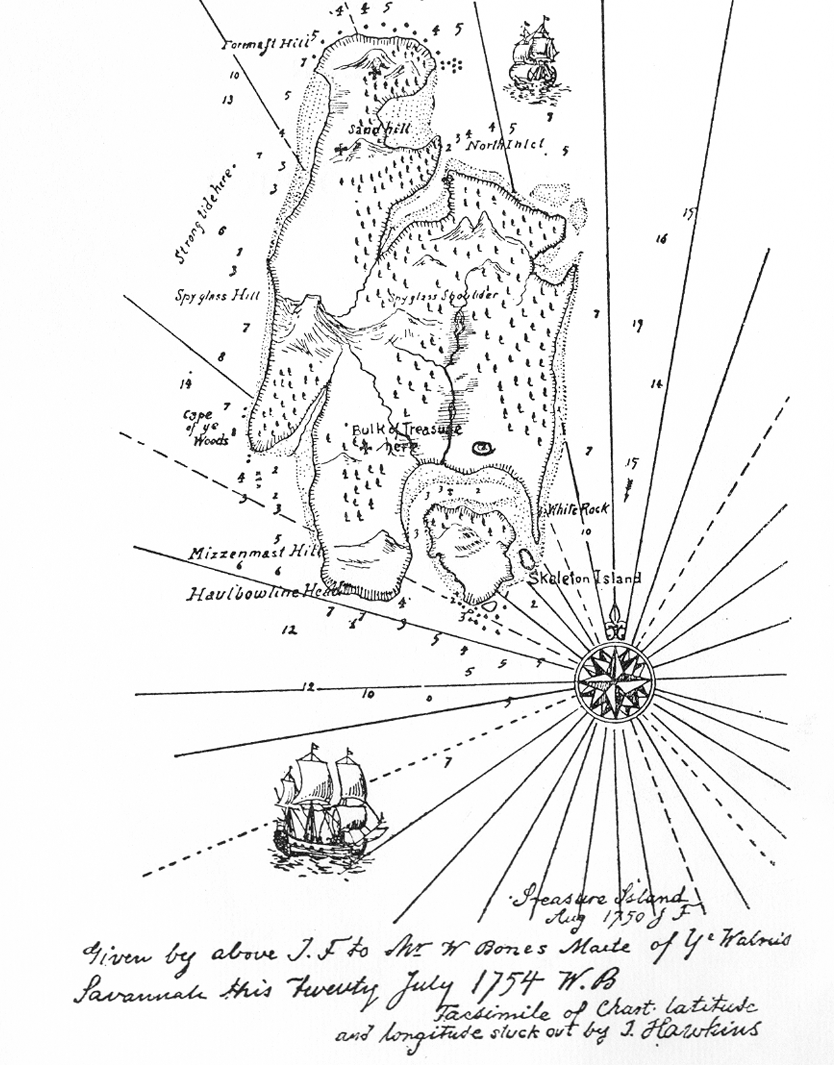

In 1837, Charles Ellms published The Pirates Own Book, which included an illustration of a prisoner falling from a “death plank” into the sea. In 1884, Robert Louis Stevenson included tales of walking the plank in his classic pirate epic, Treasure Island. And in 1887, Howard Pyle cemented the image in the popular imagination when his famous illustration “walking the plank” was published in a Harpers Weekly article.

Filmic representations, particularly during the mid-20th century, heavily featured “walking the plank” as a dramatic and suspenseful climax. Movies like “The Black Swan” (1942) and Disney’s “Peter Pan” (1953) showcased this practice, solidifying it as a staple in pirate lore.

So, what is the verdict? Considering the evidence at hand, it is highly unlikely that “walking the plank” was a widely practiced method of execution during the golden age of piracy. While pirates undoubtedly employed various forms of violence and intimidation, the historical accounts and records available do not substantiate the prevalence of this specific method.

The popularity of “walking the plank” owes more to the power of literary and cinematic imagination than to historical accuracy. It became a captivating plot device that heightened suspense and showcased the villainous nature of pirates, appealing to the audience’s desire for adventure and drama. As such, it remains an enduring symbol of the golden age of piracy, but a fictitous one. As we continue to explore and consume pirate-themed literature and media, it is crucial to appreciate the distinction between historical reality and fictional embellishments, acknowledging that the vividness of our imagination often shapes our perception of the past.